On my post this week over at evenlyoddly, I introduced the concept of counterfactuals.

Here I’m going to talk about some of the problems that contemplating counterfactuals can create for your portfolio.

I’m a lucky guy when it comes to observing how people interact with their portfolios. I get to talk to clients who used to manage their own portfolios in an endless variety of styles. Many of those clients even keep a small account for their trading and enjoyment. And many clients who trust us with the management of all of their money still want to talk about the hottest topics in the market.

Now, any client that isn’t talking to me for the first time probably knows deep down that I’m going to say that most of the market’s short-term moves are as close to random as to be indistinguishable, and that most of the headlines claiming causality are nothing more than two things that happened at the same time being blamed for each other.

So believe me when I say, the most common mistake I see people making is thinking about the investments they could have made – Amazon in 1997, Apple whenever, Bitcoin at $7K.

Their mistake and conceit is two-fold:

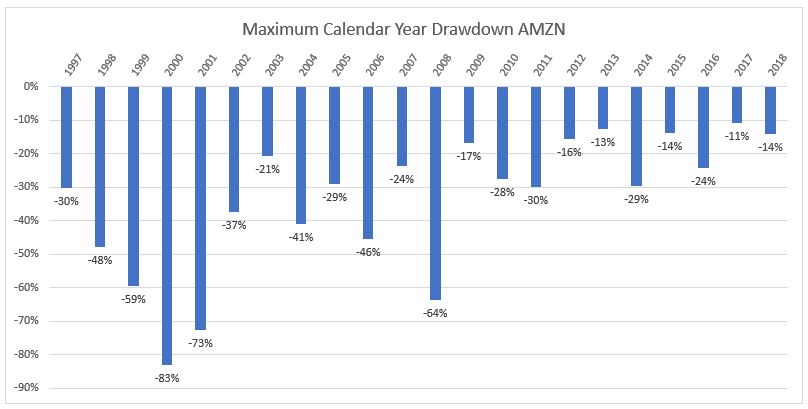

1. Not realizing that they would almost certainly have already sold if they found it to begin with. See the below graph showing the amount you would have been down at some point each calendar year from a high earlier that same year. I find it hard to believe that our investor is hodling through all of these.

source: author’s calculations, with credit to Michael Batnick, whose numbers I can confirm.

2. Not realizing that the question isn’t about picking the next winner, it’s about changing their whole decision making process so that it makes them more likely to pick the next big winner – much harder, much subtler. They are probably not considering that a strategy change aiming to hit more home runs is also prone to more strikeouts. And perhaps a worse WAR in the long-run.

Most commonly, people imagine a world in which they bought whatever the asset is at the best possible time, and are selling it right now, whenever that is, and can do all of the things that would make them happy with that new-found wealth.

The problem is that this world they are imagining doesn’t exist. If we imagine that 10 out of 10,000 possible versions of a particular investor (perhaps you) bought Amazon in 1997, 9 of them probably sold in 2001, and the other one probably continues on to invest recklessly and manages to lose the fortune shortly into the future.

There is no counterfactual world where the investor’s fantasy of having bought in 1997 and sold today and everything else stayed the same is a coherent story.