-

I was greatly influenced by monetarist ideas, particularly A Monetary History of the United States,

-

Ultimately, I decided that the gold reserve ratio was the most sensible way of thinking about the stance of monetary policy under a gold standard.

-

Obviously, “effect” cannot precede “cause”; what was actually happening was that markets were anticipating that gold market disturbances would impact future monetary policy, and this caused asset prices to respond immediately to the expected change in policy.

-

I was shocked to see so many misconceptions from the Great Depression repeated in the current crisis: 1. Assuming causality runs from financial panic to falling aggregate demand (rather than vice versa). 2. Assuming that sharply falling short-term interest rates and a sharply rising monetary base meant “easy money.” 3. Assuming that monetary policy became ineffective once rates hit zero.

-

(A modern example of this conundrum occurred when many pundits blamed the Fed for missing a housing bubble that was also missed by the financial markets.)

-

One purpose of this study is to show that monetary policy lags are much shorter than many researchers have assumed, and that both stock prices and industrial output often responded quickly to monetary shocks.

-

A recent study of the U.S. Treasury bond market showed that if one divides the trading day into five-minute intervals, virtually all of the largest price changes occur during those five-minute intervals that immediately follow government data announcements.6 There is simply no plausible explanation for this empirical regularity other than that these events are related, and that the causation runs from the data announcement to the market response.

-

Previous economic historians have missed the way that gold market instability triggered the boom and bust of 1936–1938 and have mistakenly blamed the recession on tighter fiscal policy or higher reserve requirements.

-

Keynes’s stagnation hypothesis falsely attributes problems caused by government labor market regulations to inherent defects in free-market capitalism.

-

But under a gold standard, the nominal price of gold cannot change, and thus a fall in the value of gold can only occur through a rise in the price of all other goods.

-

During the 1920s, prices were well above pre–World War I levels, and there was concern about a looming “shortage” of gold; that is, future increases in the world gold supply would not be sufficient to prevent deflation. (The term “shortage” is misleading; “scarcity” better describes the problem.)

-

If the coin be locked up in chests, it is the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated.

-

Some would argue that there is nothing the Federal Reserve could have done, but that’s not what Fed officials claim. Ben Bernanke has repeatedly emphasized that the Fed is never “out of ammunition.”

-

By mid-1928, the United States had exported almost $500 million in gold and there was a growing perception of excessive speculation in the stock market. At this time, the Fed switched to a contractionary policy aimed at restraining Wall Street’s “irrational exuberance.”

-

By March 1929 pundits were complaining that the Fed’s antispeculation policy was hurting the European economies, particularly Britain.

-

Wall Street had rallied on the reassuring news that the Bank of England had refrained from an increase in its discount rate.24 Despite what we now know about its ultimate effects, it is hard to be too critical of the Fed’s action, given that the markets seem to have made the same miscalculation.

-

While an unanticipated increase in the central bank’s target interest rate can be viewed as being contractionary on the day it is announced, over longer periods of time the nominal interest rate is an especially unreliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

-

The U.S. stock market crash so reduced the demand for credit that existing discount rates throughout the world, and even somewhat lower rates, now represented highly contractionary policies capable of dramatically increasing the world gold reserve ratio.

-

Although stocks did not fall on October 26, Bittlingmayer (p. 399) suggested that the speech’s “contents or fundamental message could have reached Wall Street a day or two earlier,

-

As the seriousness of the Depression became more apparent during 1930, opposition to the tariff spread among the public, the press, and even many business groups.

-

“tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace.”

-

suggests that the impact of German political difficulties on the U.S. markets owed more to their perceived effect on the prospects for international cooperation, than any impact they might have had on U.S. fiscal policy.

-

Interestingly, the financial press seemed to interpret the relationship between stocks and commodities differently in 1929 than in 1930. Because stock prices fell far more sharply than commodity prices in October 1929, many analysts viewed the concurrent commodity price decline as merely a symptom of the stock market crash. By mid-1930 the order of causality was usually reversed, with the commodity markets (i.e., “deflation”) seen as exerting a “depressing” influence on stocks.

-

More sophisticated observers held that declines in both markets could be attributed to monetary factors:

-

How one partitions “blame,” depends on how seriously one takes the concept of the “rules of the game” (i.e., a stable gold reserve ratio). In my view, the system was fundamentally flawed, which makes it difficult to assign blame.

-

Either the Great Depression was not forecastable in September 1929, or financial markets are not efficient.

-

Indeed, Bordo and Eichengreen (1998) showed that with more enlightened monetary policies the world monetary gold stocks were sufficient to underpin the international gold standard for several more decades.

-

The key U.S. policy error was the failure to accommodate Britain’s need to rebuild gold reserves in 1930,

-

If the Federal Reserve (Fed) had pursued an expansionary policy (a lower gold ratio), then a vigorous recovery might have occurred.

-

Contrary to popular belief, 1931 did not mark the end of the international gold standard; if it had, the Depression might have ended much more quickly. Instead, it marked the end of a stable international gold standard. For the remainder of the 1930s, a hobbled gold standard did far more damage than would have been possible from either a pure gold standard or a pure fiat money regime.

-

The price of the German war reparations bonds, dubbed “Young Plan bonds” (YPBs), were a good indicator of political turmoil in Germany during late 1930 and proved to be an even better indicator during 1931 and 1932.

-

A gold flow from the United States to France could be caused either by a reduction in the U.S. gold ratio (i.e., an expansionary policy in the United States), or an increase in France’s gold ratio (a contractionary policy in France).

-

“traders took heart on the news that the slogan of the Hitler party will be: ‘private debts—yes; reparations—no!’”

-

Britain can hardly be blamed for being among the first to recognize that gold was merely a “barbarous relic,” a view that is now widely held.

-

The most controversial question from this period is whether the Fed’s bond purchases helped mitigate an otherwise disastrous set of exogenous shocks, had no impact on the economy, or actually worsened conditions by reducing confidence and increasing hoarding.

-

The spring of 1932 was a period of severe depression and deflation, corporate default risk was soaring, and a highly aggressive open market purchase operation was driving T-bill yields to below ½ percent. This is exactly the sort of period when one would expect T-bond prices to rally. Thus, the fact that they continued to trade at well below par could be viewed as a sign that other (hidden) factors were putting upward pressure on long-term yields. One of those hidden factors was presumably fear of devaluation.

-

Under a fiat money system, fears of future inflation will reduce the demand for money, thereby causing an immediate increase in prices. Under a gold standard, however, fears of future devaluation can be deflationary.

-

the New York Times noted ironically that: It resembles the reasoning which attained much popularity in this country a year or more ago; which began by declaring that the stock market decline was the result of unfavorable trade [i.e., business] conditions, and ended by insisting still more vigorously that the trade situation was the direct result of the decline in stocks. (5/22/32,

-

They argued that the business upswing in the late summer of 1932 was a delayed reaction to the spring OMPs, and that the Fed had prematurely abandoned the OMPs. It should be clear from the analysis in this chapter that I have some problems with this view. Monetary policy may impact macroeconomic aggregates with a lag, but it is difficult to reconcile the behavior of stock and commodity prices with the Friedman-Schwartz view.

-

It is not surprising that Keynes would have confused absolute liquidity preference with the constraints of the gold standard.

-

The United States still held massive gold reserves in 1932, and there is no reason why those reserves shouldn’t have been used more aggressively in an emergency such as the Great Depression.

-

“a proper central bank does not fail because it loses all its gold in a banking crisis. It only fails if it does not.”

-

Keynes viewed a liquidity trap as a situation in which further increases in the money supply would have no impact on aggregate demand, or prices. We have no real evidence that such a trap existed in 1932.32 Instead, the problem was that the gold standard limited the amount by which central banks could increase the monetary base.

-

The biggest problem with Hsieh and Romer’s analysis is their conclusion (p. 172) that during the OMPs “virtually no sign of expectations of devaluation” surfaced. I would argue exactly the opposite.

-

Yes, the forward discounts on the dollar were never very large in any of these crises, but that simply reflects that fact that traders never viewed dollar devaluation as a particularly likely outcome, especially within the next three months.

-

Bernanke and James (1991, p. 49) provide an even more persuasive reason to doubt that real interest rates were high during the early 1930s. They pointed out that those countries that left the gold standard early (such as Britain) were able to arrest the decline in prices but continued to offer the same sort of low nominal yields on safe assets as did countries remaining on the gold standard, such as the United States and France.

-

Given the unprecedented severity of the Depression, it seems implausible that any monocausal explanation is adequate.

-

Even if the Great Contraction of 1929–1932 was essentially a monetary phenomenon, the preceding account suggests that it was monetary in the broad sense of a breakdown in the international monetary system (as emphasized by Temin and Eichengreen), rather than simply a result of inept Fed policy (the focus of Friedman and Schwartz).

-

The large increases in the world gold reserve ratio during 1929–1930, and 1931–1932 did not reflect monetary policy being constrained by the gold standard.

-

Market responses to policy shocks merely show that the markets believed that the Fed was likely to act as if it felt constrained by potential gold outflows.

-

it doesn’t quite matter whether it was fiscal or monetary policy that caused this crisis. In either case the net effect of the crisis was to weaken the impact of countercyclical policy.

-

Are we accusing countries of violating well-agreed-upon ground rules (like a player cheating in a sports competition) or are we accusing countries of adopting ill-advised policies that hurt others and themselves?

-

In a sense, the interwar gold standard was both too flexible and not flexible enough. A rigid adherence to a fixed gold reserve ratio would have greatly reduced central bank hoarding during the early 1930s. Alternatively, a much more flexible regime which completely disregarded the gold reserve ratio would have allowed central banks to more easily cooperate to economize on the demand for monetary gold during a deflationary crisis.

-

But the policymakers of that era (particularly in America) were living in a world where devaluation seemed almost inconceivable. The entrenchment of the gold standard regime in America helps explain why the financial markets placed such high hopes on the possibility of international monetary cooperation, despite the ultimate ineffectiveness of those initiatives. They saw it as the only game in town.

-

Even our best-selling money textbooks emphasize the unreliability of interest rates as monetary policy indicators: It is dangerous always to associate the easing or the tightening of monetary policy with a fall or a rise in short-term nominal interest rates. (Mishkin, 2007, p. 606)

-

Not so long ago, economists liked to make fun of statements such as Joan Robinson’s claim that easy money couldn’t have caused the German hyperinflation as (she argued) nominal interest rates weren’t low.

-

Unfortunately, most economists seemed to miss the monetary nature of the second and more severe phase of the recent crisis, which began in mid-2008. Nominal GDP fell nearly 4 percent over the following twelve months, to a level more than 9 percent below trend.

-

To those closest to the problem, a severe fall in aggregate demand, or nominal GDP, almost never looks like it was caused by monetary policy. It is likely to be accompanied by very low nominal rates, and a bloated monetary base (as people and banks hoard currency). That looks like “easy money” to the untrained eye.

-

In the late 1990s, Milton Friedman also complained that modern economists had not really absorbed the lessons of the Great Depression: Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy… . After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die. (Friedman, 1998.)

Links from the last quarter of 2016:

- Excessive debt vs. current account deficits: Confusing the two is the arena of goldbugs, journos, and first year college students.

The US has been running large current account deficits for many decades. Commenters often suggest that this means we are becoming a debtor nation, living beyond our means. This is not true.

- The economics of France: France’s problems seem to be a lot more about inability to fire people than government spending per se (though I bet they are related).

As a result, France’s higher productivity is in part because a substantial share of those who would tend be the lower-productivity workers (like young workers, for example) just aren’t working at all.

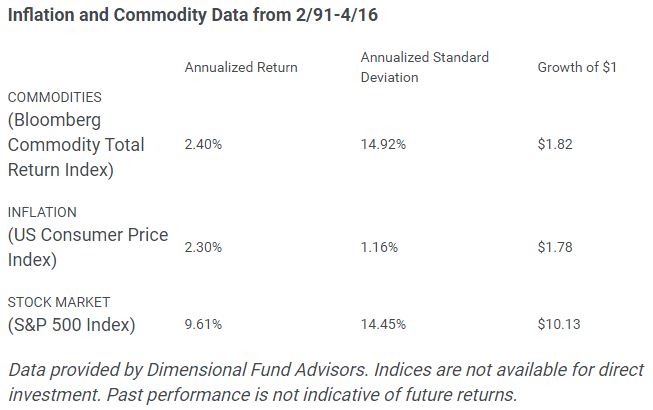

- As we all know, gold is a pet rock, and commodities suck: Want the standard deviation of the S&P 500 with returns that barely match inflation? I’ve got a pile of yellow metal to sell you.

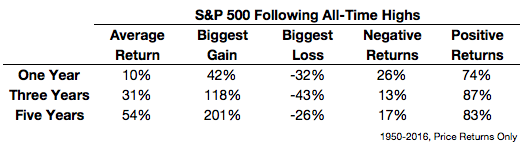

- Should you sell at Dow 20,000? It’s an all-time high after all: Of course not, because you’re smart and realize that if something goes up and to the right over time, being upper and righter than ever before is not an exception, it’s the rule.

- White supremacists make up effectively none of Trump’s supporters: “The left” has been handling itself extremely poorly throughout this entire election cycle, and things haven’t changed post-election. Trump might be a pathological narcissist with no qualifications, but if you cry “Hitler” enough times, don’t be surprised when nobody hears you.

7. What about the border wall? Doesn’t that mean Trump must hate Mexicans?

As multiplesources point out, both Hillary and Obama voted for the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which put up a 700 mile fence along the US-Mexican border. Politifact says that Hillary and Obama wanted a 700 mile fence but Trump wants a 1000 mile wall, so these are totally different. But really? Support a 700 mile fence, and you’re the champion of diversity and all that is right in the world; support a 1000 mile wall and there’s no possible explanation besides white nationalism?

- AI is learning everything: I have a bet with Bruns that DeepMind won’t beat a top Starcraft player before 11.05.2020.

The AI vastly outperformed a professional lip-reader who attempted to decipher 200 randomly selected clips from the data set.

The professional annotated just 12.4 per cent of words without any error. But the AI annotated 46.8 per cent of all words in the March to September data set without any error. And many of its mistakes were small slips, like missing an ‘s’ at the end of a word. With these results, the system also outperforms all other automatic lip-reading systems.

- Xenophobia vs. Racism: I didn’t think of it until now, but it’s obvious that acceptable xenophobia is often spun into unacceptable racism depending on what a journalist or pitchfork carrier is going for.

But aren’t people in every country – Canada included – similarly unreasonable and unfair? Sure. Xenophobia – not racism – is the unrepentant bigotry that rules the world. People in every country on Earth take it for granted. But as we teach our children, “Everyone else is doing it” is no excuse for bad behavior. Almost everyone is is extremely xenophobic. And everyone should stop. Starting with you.

- School Vouchers: This is one of those areas where pretty much everybody who I think is smart agrees that giving people choice in where to send their kids will have more good outcomes than bad, but the US is such a huge country that it is overwhelming to think about where to start. The link here is a rebuttal to one of the most common arguments against vouchers, which is that the profit motive would naturally cause shareholders to gain at the expense of the yutes.

The third theory is Wilde’s Law: “The bureaucracy is expanding to meet the needs of the expanding bureaucracy.”

Sign-up for email alerts below:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

A guy I like to follow, Jon Favreau, recently linked an article from AP titled: “Trump voter lost her home to new treasury secretary”.

There is so much wrong with this article that I scarcely know where to start. First of all, I get it, that headlines are sometimes sensationalized, and that there is a very appealing chance of going viral by having a bit of left-leaning schadenfreude. As far as I can tell from the article itself, the only thing accurate about the headline is that the woman in question voted for Trump.

Let’s dig in a bit.

OneWest, a bank formerly owned by a group of investors headed by Mnuchin, had foreclosed on her Los Angeles-area home in the aftermath of the Great Recession, stripping her of the two units she rented as a primary source of income.

Slowly now: a branch of a bank that made her a loan foreclosed on that loan after she couldn’t pay it. Mnuchin and many others, including notably excluded George Soros and John Paulson invested in OneWest after it filed bankruptcy in 2009.

The kicker, this wasn’t even just a primary residence, she rented out two units. On at least some level, this was an investment property.

Interpretation later confirmed, she took on more debt to increase her rental portfolio:

She rented out two of the units and lived in the third. Colebrook refinanced her mortgage in order to renovate the property and help buy additional homes to generate rental income.

So what exactly was the problem?

By the time the financial crisis struck in 2008, she had an interest-only mortgage on the triplex known as a “pick-a-payment” loan. Her monthly payments ran as high as $2,000 and only covered the interest on the debt.

Now, I don’t know the details of the contract that the person in question had with the bank, but let’s assume it was close to market, which would have meant a rate at or below 5% by that point. If she’s making monthly payments of $2,000, she owes about half a million bucks. From earlier in the article:

In 1998, she bought a triplex for $248,000 in Hawthorne, California, not too far from Los Angeles International Airport.

Admittedly, I can’t tell if this is the triplex we’re talking about, because the writing is bad and vague, but I assume it’s not some bait and switch.

So she took out about twice as much debt as the original value of the property to make more investments. What happened next?

“All my tenants lost their jobs in the crash,” Colebrook said. “They couldn’t pay. It was a knock-on effect.”

This has literally been the risk of owning rental real estate since the beginning of time, that your tenants will not be able to pay. It has almost nothing to do with OneWest, who would have much preferred she just pay her mortgage, and even less to do with Mnuchin. This is exactly what banks do.

So what’s the moral of the story? That if you lever up with as much money as anybody will let you borrow to buy more investments that you might get hurt if there’s an economic downturn? That Mnuchin is part of some terrible group of people for being part of a group and buying a bank at auction after the crisis and then running it like a bank?

One final point (the voter talking about Trump):

“He doesn’t want the truth,” she said. “He’s now backing his buddies.”.

In 2004, he founded a hedge fund, Dune Capital Management, named for a spot near his house in the Hamptons. The firm invested in at least two Donald Trump projects and, in one of them, was sued by Trump before a settlement was reached.

I can’t take this garbage form of journalism seriously. It said absolutely nothing, mixed facts with commentary, ignored the economic realities of life, and had a title that bore little resemblance to the facts.

It’s more important than ever to be a critical reader of what articles actually say. Blindly trusting headlines to be accurate has never been a good way to form opinions or consume information, but in 2016 that’s more true than ever. When it comes to ‘fake news’, as far as I’m concerned, pieces with no connection to reality are just as bad as total fabrications, at least lies are easier to spot.

Disclaimer: I didn’t vote for Trump, but don’t have any sympathy for people surprised that the man without a plan isn’t doing things the way they expected.

- The Economist on who is hurt most by protectionist policies: (hint): if you buy more from China, you benefit more.

But the poorest 10% of consumers would lose 63% of their spending power, because they buy relatively more imported goods. The authors find a bias of trade in favour of poorer people in all 40 countries in their study, which included 13 developing countries.

- Kevin Erdmann with a hilarious post about the shape of the housing demand curve: if only enough people would realize the implications, we might solve a lot of problems.

- David Henderson points out the terrible reporting on Trump’s taxes: I’m glad he noticed what I did, that the reporting was sloppy, stupid, and didn’t mean a goddamn thing. I guess they did the best they could with a big loss as the “smoking gun”, but all the parading around of the meaningless 18 year number was a farce.

They hired people–and, notice, more than one–to tell them that when you have a big loss in one year, you can use it to offset income

- Berkeley shutters free programs after DOJ comes after them for not having subtitles and therefore being non-ADA compliant: I have mixed feelings and I’m not sure why, but mostly I think this is a terrible loss.

In many cases the requirements proposed by the department would require the university to implement extremely expensive measures to continue to make these resources available to the public for free.

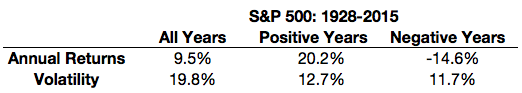

- Ben Carlson on Risk Taking: One point that is often lost on people is that years ‘far away’ from the mean are normal, not the other way around.

Need more amazing links to yo inbox? Sign up below:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto)

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

![Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto) by [Taleb, Nassim Nicholas]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/412CsqHl9eL.jpg)

- I’d rather be dumb and antifragile than extremely smart and fragile, any time.

- Which brings us to the largest fragilizer of society, and greatest generator of crises, absence of “skin in the game.”

- Black Swans hijack our brains, making us feel we “sort of” or “almost” predicted them, because they are retrospectively explainable.

- An annoying aspect of the Black Swan problem—in fact the central, and largely missed, point—is that the odds of rare events are simply not computable.

- In short, the fragilista (medical, economic, social planning) is one who makes you engage in policies and actions, all artificial, in which the benefits are small and visible, and the side effects potentially severe and invisible.

- no skill to understand it, mastery to write it.

- To accord with the practitioner’s ethos, the rule in this book is as follows: I eat my own cooking.

- philosophical notion of doxastic commitment, a class of beliefs that go beyond talk, and to which we are committed enough to take personal risks.

- Hormesis, a word coined by pharmacologists, is when a small dose of a harmful substance is actually beneficial for the organism, acting as medicine.

- I have called this mental defect the Lucretius problem, after the Latin poetic philosopher who wrote that the fool believes that the tallest mountain in the world will be equal to the tallest one he has observed.

- You know, this economist had what is called a tête à baffe, a face that invites you to slap it, just like a cannoli invites you to bite into it.

- Finally, a thought. He who has never sinned is less reliable than he who has only sinned once. And someone who has made plenty of errors—though never the same error more than once—is more reliable than someone who has never made any.

- treating an organism like a simple machine is a kind of simplification or approximation or reduction that is exactly like a Procrustean bed.

- employees, who have no volatility, but can be surprised to see their income going to zero after a phone call from the personnel department.

- if you supply a typical copy editor with a text, he will propose a certain number of edits, say about five changes per page. Now accept his “corrections” and give this text to another copy editor who tends to have the same average rate of intervention (editors vary in interventionism), and you will see that he will suggest an equivalent number of edits, sometimes reversing changes made by the previous editor. Find a third editor, same.

- Over my writing career I’ve noticed that those who overedit tend to miss the real typos (and vice versa). I once pulled an op-ed from The Washington Post owing to the abundance of completely unnecessary edits, as if every word had been replaced by a synonym from the thesaurus. I gave the article to the Financial Times instead. The editor there made one single correction: 1989 became 1990. The Washington Post had tried so hard that they missed the only relevant mistake.

- Restaurants do not take your order, then cut the cake and the steak in small pieces and mix the whole thing together with those machines that produce a lot of noise. Activities “in the middle” are like such mashing.

- “Provide for the worst; the best can take care of itself.”

- people tend to provide for the best and hope that the worst will take care of itself.

- I am fond of the brand of the unexpected one finds at parties (going to parties has optionality, perhaps the best advice for someone who wants to benefit from uncertainty with low downside).

- For if you think that education causes wealth, rather than being a result of wealth, or that intelligent actions and discoveries are the result of intelligent ideas, you will be in for a surprise.

- As per the Yiddish saying: “If the student is smart, the teacher takes the credit.” These illusions of contribution result largely from confirmation fallacies:

- You would think that the people who specialized in foreign exchange understood economics, geopolitics, mathematics, the future price of currencies, differentials between prices in countries. Or that they read assiduously the economics reports published in glossy papers by various institutes. You might also imagine cosmopolitan fellows who wear ascots at the opera on Saturday night, make wine sommeliers nervous, and take tango lessons on Wednesday afternoons. Or spoke intelligible English. None of that.

- Theory should stay independent from practice and vice versa—and we should not extract academic economists from their campuses and put them in positions of decision making. Economics is not a science and should not be there to advise policy.

- As Yogi Berra said, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice; in practice there is.”

- the fragilista who mistakes what he does not understand for nonsense.

- charlatans are recognizable in that they will give you positive advice, and only positive advice, exploiting our gullibility and sucker-proneness for recipes that hit you in a flash as just obvious, then evaporate later as you forget them. Just look at the “how to” books with, in their title, “Ten Steps for—” (fill in: enrichment, weight loss, making friends, innovation, getting elected, building muscles, finding a husband, running an orphanage, etc.). Yet in practice it is the negative that’s used by the pros,

- For the Arab scholar and religious leader Ali Bin Abi-Taleb (no relation), keeping one’s distance from an ignorant person is equivalent to keeping company with a wise man.

- Urban planning, incidentally, demonstrates the central property of the so-called top-down effect: top-down is usually irreversible, so mistakes tend to stick, whereas bottom-up is gradual and incremental, with creation and destruction along the way, though presumably with a positive slope.

- “do you have evidence that this is harmful?” (the same type of response as “is there evidence that polluting is harmful?”). As usual, the solution is simple, an extension of via negativa and Fat Tony’s don’t-be-a-sucker rule: the non-natural needs to prove its benefits, not the natural—

- Second principle of iatrogenics: it is not linear. We should not take risks with near-healthy people; but we should take a lot, a lot more risks with those deemed in danger.

- Religion has invisible purposes beyond what the literal-minded scientistic-scientifiers identify—one of which is to protect us from scientism, that is, them. We can see in the corpus of inscriptions (on graves) accounts of people erecting fountains or even temples to their favorite gods after these succeeded where doctors failed.

- I believe in the heuristics of religion and blindly accommodate its rules (as an Orthodox Christian, I can cheat once in a while, as it is part of the game).

- For the Romans, engineers needed to spend some time under the bridge they built—something that should be required of financial engineers today.

- Words are dangerous: postdictors, who explain things after the fact—because they are in the business of talking—always look smarter than predictors.

- Anything one needs to market heavily is necessarily either an inferior product or an evil one.

- my experience is that most journalists, professional academics, and other in similar phony professions don’t read original sources, but each other, largely because they need to figure out the consensus before making a pronouncement.

- First, the more complicated the regulation, the more prone to arbitrages by insiders. This is another argument in favor of heuristics.

- Everything gains or loses from volatility. Fragility is what loses from volatility and uncertainty.

Back at it again with the fresh links:

- John Hempton (whose status has absolutely blown up over the past several months/years, maybe thanks to HLF?) on investment philosophy: A really interesting take on Buffett’s famous ‘punch card’ framework, which I find really useful outside of investing as well.

A twenty punch card investment portfolio is – by its nature – a concentrated investment portfolio. If I had run my portfolio like that I would have come out of the crisis with maybe six stocks, turfed one or two by now and added a single stock in 2012.

- Scott Sumner on whether central banks are out of ammo: If you know anything about Scott you already know the answer.

1. The Fed raised rates last December, and just a week ago indicated that it is likely to raise rates again later this year. Is that doing your best to inflate?

2. The ECB and the BOJ have mostly disappointed markets this year, offering up one announcement after another that was less expansionary than markets expected.

So no, they are not doing their best. If at some point they do in fact do their best, and still come up short, then by all means given them help.

- Another pop-psychology phenom bites the dust. This time it is “power poses”: If it has a Ted talk devoted to it, it’s probably over-hyped. Huge props to Carney for putting this out there, lends credibility like nothing else he could do.

I continue to be a reviewer on failed replications and re-analyses of the data — signing my reviews as I did in the Ranehill et al. (2015) case — almost always in favor of publication (I was strongly in favor in the Ranehill case). More failed replications are making their way through the publication process. We will see them soon. The evidence against the existence of power poses is undeniable.

- Double dose of Sumner, this time on Trump’s economic plan: This is easily the most embarrassing set of economic proposals a Republican candidate has had in memory for me.

A poster child for this problem is China and its narrowly pegged currency. In a world of freely floating currencies, the US dollar would weaken and the Chinese yuan would strengthen because the US runs a large trade deficit with China and the rest of the world.

Where does one start? No, China is not intervening to lower the value of the yuan; they are intervening to raise its value. And no, textbook theory does not say that exchange rates should adjust in the long run to balance trade in goods and services, unless long run means 1,000,000,000 years, in present value terms. But in that case the current US deficit presents no puzzle; it hasn’t lasted for a billion years.

Notice the schoolmarmy “And Trump still has not apologized to the president of the United States for an effort that many African-Americans saw as an effort to delegitimize the first black president.” As if that is relevant to a fact check.

Our findings provide empirical evidence that ride-sharing services such as Uber significantly decrease the traffic congestion after entering an urban area.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2838043

- David Henderson again, this time on the weak “arguments” from the Boston Globe’s Renee Loth against legalization of marijuana: calling out poor reasoning is a public service.

In other words, she would prefer to purposely make some other people worse off with higher taxes on what they buy (sales taxes) or earn (income taxes) than to raise the same amount of revenue by raising no taxes but instead legalizing a good so that the revenues are taken from people who are better off paying the revenues than buying in an illegal world.

That’s either ignorant or cruel, or both.

Books: I read a bunch of these little time sinks recently:

Get A Grip: One of a seemingly endless stream of fable-centric business management books. This one is about the “Entrepreneurial Operating System” that comes from an eponymous consulting group. Seems to be in the zeitgeist. More concrete than most other fabley books, and interesting take on the really popular notion of getting the right people on the bus then finding their seat later — basically defines seats on the bus first and then goes to fill them.

![Get A Grip: An Entrepreneurial Fable . . . Your Journey to Get Real, Get Simple, and Get Results by [Wickman, Gino, Paton, Mike]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51EYbQRFc-L.jpg)

Antifragile: Classic Taleb book, I’m thinking of doing a new kind of post on this one.

![Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto) by [Taleb, Nassim Nicholas]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/412CsqHl9eL.jpg)

The Ideal Team Player: Another business fable, this one from the Table Group, all about their three ‘virtues’, being humble, hungry, and smart. It may be because I haven’t read any of the other books in the series for a while, but I was more impressed than I thought I would be with their definitions of the virtues.

Humble is about not being arrogant, but also not being over-modest. Subtle distinction that I was surprised they made.

Hungry is pretty straight forward, and I liked that they mentioned that a candidate mentioning ‘work-life balance’ too many times is a red flag. All businesses want to think they let their employees find balance, but hiring someone who is focused on how much they won’t have to work is questionable.

Smart is focused on being people-smart, and people who can’t take social cues are undesirable as teammates.

As per usual for Lencioni, there were about a dozen awkward references to prayer, completely unrelated to the story, which I could have done without.

![The Ideal Team Player: How to Recognize and Cultivate The Three Essential Virtues by [Lencioni, Patrick M.]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/5174ox9CxwL.jpg)

Like the links? Get them straight at yo face as soon as they are published:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

Two weeks worth of links because I was gone at conferences last week — XYPN and FinCon. Summary posts to come.

- NYT Article on Chilean Pensions: Spoiler: they are very small. Disclaimer: I know very little about the political/financial history of Chile. This is a perfect example of a totally worthless article, not because it is poorly written, but because there is absolutely no clue given as to the root cause of the problem. Yes, I get it, the pensions are low, but is that because contributions were low? fees were high? returns were low? payouts are below market? The article paints Chileans in a terrible light, it reads to me as if they are asking for more money because what they saved isn’t enough, and that the retirees are demanding the government take from the young to give to the old. A poor country isn’t going to magically be able to let citizens retire at the standard of living of a rich country because it’s a nice thing to do.

“The A.F.P.s have never lost money, stolen money or gone bankrupt,” Mr. Pérez said. “Does that mean that pensions are good? No, they are not. The system needs important changes. But the A.F.P.s administer the funds of those who save, and they’ve done that very well.”

- NatGeo on BASE jumpers dying in record numbers: Super interesting article on a pretty glamorous sport. To answer the titular question, it’s pretty obvious that more people are dying because more people are doing it, it doesn’t seem like BASE jumping (sans wingsuit) has gotten much more dangerous.

Clif Bar’s official statement read that it was no longer comfortable “benefitting from the amount of risk certain athletes are taking in areas of the sport where there is no margin for error; where there is no safety net.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum are companies like Red Bull, GoPro, and, most recently, Stride Gum—which backed a skydiving stunt this summer in which Luke Aikens jumped out of a plane without a parachuteand landed in a large net.

- David Henderson enlightens on trade deficits vs. risky/innovative enterprise: I’m really glad he made this clarifying post, because when I read the original writing by Tyler Cowen, I had the thought that it seems very unlikely that foreign purchases of treasuries are somehow crowding out private investment in business, and simply left it there.

If foreigners buy more bonds, then Americans buy fewer bonds and invest in those “risky, innovative enterprises.” So it’s hard to see why foreigners buying bonds means that there’s less investment in those enterprises.

Now it’s quite possible that the higher U.S. federal budget deficit crowds out investment in those enterprises. But then it’s the U.S. budget deficit doing that, not the foreigners’ choice of U.S. assets to invest in.

For those who are offended by surge pricing at a time of crisis, please tell me your preferred method for getting some people (drivers) to head toward danger when everyone else prefers to head in the other direction. And then tell me how you are going to get people who are heading out to the grocery or are thinking of going out for a drink to postpone or cancel their plans.

- Awesome article on how Seattle killed micro-housing from David Neiman: I have got to think that one of these highly desirable west coast cities is going to avoid the nimby-ism trap and will at least join the ranks of SF/LA/Seattle if not eclipsing them entirely as the wealthy, progressive, growing places to be.

But at least you are in the MFTE program, so five of your apartments will offer a discounted rent of $1,020 per month to people whose incomes qualify. (You facepalm in disbelief, however, that whereas your original plan offered 40 units, unsubsidized, at $900 a month, your new version has just five units, subsidized, at $1,020.)

For the dopest links straight at your inbox, sign up below:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

Short links this week, China and monetary policy are two areas that almost anyone who considers themselves financially savvy probably has an opinion in which they are too confident by a factor of 10.

- Timothy Taylor discusses a paper by Kirkegaard about Chinese education plateauing: Both the paper and Taylor’s analysis put a slightly more pessimistic spin on things than I would have. China is becoming educated and people are reaping the rewards, soon they will realize they need more education to get the same rewards their parents got, and the next generations will act accordingly.

- Scott Sumner discusses the current monetary environment and how various schools of economic thought vary in their explanations: Given my own strong monetarist leanings, I think the descriptions of the other schools are fair, though maybe they are less charitable than I think.

I for one still believe that low rates (and/or QE) don’t mean easy money, that monetary policy is still highly effective at zero rates, that fiscal policy is mostly ineffective, even at zero rates, that level targeting is especially beneficial at the zero bound, that central banks should target the market forecast, that markets are efficient…

Sign up for more links below:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

- Scott Sumner on monetary offset: Understanding the implications of monetary offset is one of the prerequisites for intelligent conversation of economics.

There are so many fallacies here one hardly knows where to begin. The central banks have not done any “heavy lifting”. They can print money at virtually zero cost and their massive portfolio of bonds is generating enormous profits, more than twice as large as before the recession.

- NYT article on Uber drivers becoming more homo economicus-ish: I know there are a million economists who would kill to get their hands on the data that Uber has, I’m sure there are many more behavioral theories that could be tested.

Henry Farber, a Princeton economist and author of several studiesaffirming the traditional view, echoed this sentiment, saying even his papers suggest that beginners frequently do not drive enough when business is brisk. “New drivers who can’t figure it out leave the business,” he said. “The ones who stay tend to learn.”

- WCI on investing a lump sum in your 80s: good analysis and one of the classic examples of the potential usefulness of immediate annuities. Though of course the point is well made that he could simply live off of the cash for 17 years. The common mistake people make in this spot that I see is trying to protect the principal, stretching for excess dividend/interest yield to meet their 6% need.

While the income need/portfolio size ratio (6%) might not seem large to a 60 year old, it is quite good for an 83 year old.

- Your monthly ‘fails to replicate’ post: this time, that one about smiling making you happier. Have those studies on ‘power poses’ failed to replicate yet?

But now an attempt to replicate this modern classic of psychology research, involving 17 labs around the world and a collective subject pool of 1894 students, has failed. “Overall, the results were inconsistent with the original result,” the researchers said.

Sign up for links straight to your inbox below:

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]

- Joseph Belth on Long Term Care Insurance: Whether Long Term Care Insurance (LTCI) is necessary or wise is a common question when people are nearing retirement. The topic deserves a more thorough treatment than a links blurb, but the article gives a taste of why many savvy people choose to self-insure (i.e. not buy insurance) rather than shell out for LTCI coverage.

“Your premiums will never increase because of your age or any changes in your health.” I wrote to the company expressing concern that the sentence, although technically correct, was deceptive. I said the letter should make clear that the company has the right to increase premiums on a class basis.

- Low Interest Rates: Not Easy Money: For years I’ve been cautioning very smart people that I don’t know of a reason why interest rates are bound to return to ‘normal levels’, whatever that means.

Of course if that were true, then the Fed tightening of last December would have led to higher interest rates. Instead, bond yields have fallen sharply over the past 8 months.

- How Long Do 65 Year Olds Live?: Having a basic understanding of the current landscape for people entering retirement is a prerequisite if one wants to discuss the finances and economics that accompany them. Great primer from Wade Pfau here.

Sign up for more links.

[newsletters_subscribe list=”1″]