-

I make two provocative claims in these three chapters. First, that in the absence of other policy initiatives, the devaluation of the dollar might have essentially ended the Depression by late 1934.

-

And second, that Roosevelt’s policy of increasing wages may have extended the Depression by nearly seven years and thus caused roughly half of all man-years of unemployment during the period from 1929 to 1941.

-

serious doubts arose as to the expansionary potential of monetary policies implemented in an environment where some linkage to gold was maintained.

-

The causality probably ran both ways, with banking troubles leading to fears of devaluation, and fears of devaluation leading to currency hoarding, and thereby triggering more banking holidays.

-

It is also important to recall that during this period, the federal government was perceived by investors as having a much greater ability to influence real asset prices than is the case today.

-

Yet, the only discernable macroeconomic consequence of this crisis would be a modest dip in industrial production during March 1933.

-

Even in the 1930s, it was widely understood that financial markets were not capable of withstanding great uncertainty over the soundness of a currency. That is why it was (and still is) standard operating procedure for policymakers to deny any intention of devaluation right up to the last minute.

-

now able to adopt expansionary policies without fear of a run on the U.S. gold stocks, markets reverted to their traditional pattern of welcoming lower discount rates.

-

one could argue that when deciding whether to construct a new building what matters is the expected price at which one can sell or rent the project, not the current rents paid by tenants under long-term contracts.

-

In the next chapter we will see how a mere two weeks after FDR torpedoed the World Monetary Conference, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) began to force wages much higher, which negated most of the benefits flowing from the policy of dollar depreciation.

-

I hope to show that the impact of the NIRA was much greater than almost anyone else has suspected—preventing what otherwise would have been a near full recovery by late 1934 or early 1935.

-

It is interesting to update Fisher’s model to the 1923–1935 period. The correlation between predicted output and actual output falls from .941 during 1915–1922, to .256 during 1923–1935.

-

The primary purpose of the NIRA was to establish industrial codes that would serve to prevent “ruinous” competition by setting minimum levels for wages and prices.

-

Consider the following hypothesis: rather than being a single event, “the” Great Depression was actually two distinction depressions. The first, demandside depression, ended in late 1934, by which time output had returned to its “natural rate.” A second, supply-side depression, began in late July 1933, sharply depressed the natural rate of output, and lasted for eight more years.

-

although real wages were highly countercyclical throughout the entire interwar period, nominal wages were essentially acyclical between 1920 and 1933 (when labor markets were relatively unregulated) and then became highly countercyclical for the remainder of the 1930s. In other words, higher wages don’t reduce output when they reflect market forces (such as productivity gains) but do depress output when they reflect nonmarket factors. Although hardly definitive, this pattern is exactly what one would expect if New Deal policies began generating autonomous wage shocks in 1933.

-

The “new information” received from July 19 to 21 was not precisely a 22.3 percent wage shock but rather an increase in the perceived likelihood of such a shock. This means that the three-day stock price collapse may significantly understate the overall impact of the Blue Eagle program on equity values.

-

A few have gone even further than Temin and Wigmore, arguing that the NIRA and AAA may have actually contributed to the recovery from the Depression.

-

A second difference is that most studies have relied on quarterly or annual data, not monthly data. Even using quarterly data, the production spike in July 1933 seems far less dramatic, and with annual data, this mini-business cycle is completely obscured.

-

I have argued that both dollar devaluation and the NIRA had extraordinarily powerful effects on output, but that the two policies roughly cancelled each other out.28 This means that a researcher focusing on monetary policy might see only modest evidence of the expansionary potential of the dollar depreciation program. Similarly, someone focusing only on the NIRA would tend to underestimate its contractionary impact.

-

And even if researchers did look at both monetary and wage policy, they may have used the wrong indicator of monetary policy. For instance, Weinstein (1981) did observe that in the absence of the NIRA, monetary expansion should have led to even more rapid economic growth during the mid-1930s. But Weinstein relied on money supply figures as a policy indicator, rather than the price of gold, and thus greatly underestimated the extent of monetary stimulus in 1933.

-

And finally, many other researchers seem to have underestimated the U.S. economy’s ability to self-correct. Great Contractions are so rare that we don’t really know much about the economy’s properties at 25 percent unemployment. Although economists sympathetic to Roosevelt often point out that recovery from the Depression was rapid, I cannot help agreeing with Cole and Ohanian’s (2004) view that the recovery was surprisingly anemic.

-

the United States was not “forced” off the gold standard; in fact, its holdings of gold were the largest in the world. Rather, the decision to talk down the value of the dollar was made pursuant to the broader macroeconomic objectives of the Roosevelt administration

-

On September 21, a New York Times headline reported that “ROOSEVELT CHECKS INFLATION DEMAND.”4 Stocks fell by a total of 7.7 percent on September 20 and 21, and the following day’s New York Times (p. 27) attributed the decline to “the disappointment of those traders who had counted too heavily of the prospect of currency inflation.”

-

To a much greater extent than today, the (inverse of the) price of gold was viewed as the value of the dollar.

-

If Roosevelt did operate under the assumption that any legal devaluation was likely to be permanent, then he would naturally have been reluctant to firmly commit to a new par value until it was clear that this value would be consistent with his price level objectives. When viewed from this perspective, Roosevelt’s policy options were quite limited. The traditional tools of monetary policy included discount loans and open market operations, but these were under the control of the Federal Reserve.

-

The November 17 New York Times (p. 2) reported rumors that President Roosevelt was trying to force France off the gold standard. Even if this story was fictitious, there is little doubt that the policy of dollar depreciation was putting the franc under great stress, and this was during a period when budgetary problems in France had already caused an outflow of foreign capital.

-

Recall that immediately after the dollar began depreciating in April, prices rose sharply while nominal wages were almost unchanged,

-

Under these circumstances, price level increases would raise nominal stock prices by pushing up the nominal value of corporate assets and could raise real stock prices if the higher commodity prices led to expectations of economic recovery.

-

Roosevelt listened to a variety of advisors and occasionally supported mutually incompatible policies.

-

It would be extremely difficult to discriminate between the gold hoarding caused by fear of dollar depreciation and hoarding due to factors such as fear of French devaluation.

-

Pearson, Myers, and Gans quote Warren’s notes to the effect that when the summer of 1934 arrived without substantial increases in commodity prices: The President (a) wanted more inflation and (b) assumed or had been led to believe that there was a long lag in the effect of depreciation. He did not understand—as many others did not then and do not now—the principle that commodity prices respond immediately to changes in the price of gold. (1957, p. 5664)

-

Most modern macroeconomists continue to make this mistake, taking a wait and see attitude toward initiatives such as “quantitative easing,” whereas the inflation expectations embedded in the Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) markets provided immediate evidence that the policy was nowhere near sufficient.

-

1933 contained not one, but two of the most dramatic policy experiments ever conducted by the U.S. government.

-

Another important lesson from 1933 is that the only avowedly inflationary policy ever pursued by the United States was accompanied by rapid inflation in all of the price indices, despite high unemployment.

-

And the fact that the recovery aborted immediately following a government-mandated 22 percent wage increase (a classic adverse supply shock) provides additional confirmation of the basic aggregate supply/aggregate demand (AS/AD) model.

-

Mankiw and Reis identify “three key facts” of modern business cycle theory: 1. “The Acceleration Phenomenon … inflation tends to rise when the economy is booming and falls when economic activity is depressed.” 2. “The Smoothness of Real Wages … real wages do not fluctuate as much as labor productivity.” 3. “Gradual Response of Real Variables … The full impact of shocks is usually felt only after several quarters.” (2006, p. 164)

-

In the preceding three chapters we have seen evidence of rapid inflation in an extremely depressed economy, rapid change in real wages (even before implementation of the NIRA), and industrial production responding almost immediately to monetary shocks.

-

Monetary policy doesn’t get much more exogenous than this: One morning (it was Friday, November 3), when Morgenthau came to the bedside tense with worry over some pressing problem and suggested that the [gold] price change that day be considerably greater than the 10 to 15 cents of immediately preceding days, Roosevelt promptly announced that the increase would be 21 cents. Why that figure? Because “three times seven” is a lucky number, said Roosevelt, his face straight but his blue eyes twinkling at Morgenthau’s recoil from such frivolous dealing with a serious matter (quoted in Davis, 1986, p. 294)

-

There are three generally accepted characteristics of a gold standard: maintenance of a fixed price of gold, free convertibility of the currency into gold, and adherence to the rules of the game—that is, a relatively stable gold reserve ratio. While prior to 1933, the United States did conform to the first two criteria, it did not even come close to adhering to the rules of the game. After 1934, the dollar was no longer freely convertible into gold, but its market price was still fixed, and changes in the monetary base were closely correlated with changes in the monetary gold stock.

-

In this account of the Great Depression, the two-and-a-half year period from February 1934 to September 1936 represents the eye of the hurricane. The purchasing power of gold was fairly stable, and (because the dollar was pegged to gold) a stable gold market meant a relatively stable price level. As gold flowed back from the gold bloc to the United States, the world gold reserve ratio declined. Thus, the deflationary impact of private gold hoarding (as well as currency hoarding) was roughly offset by the inflationary impact of gold flows.

-

From this perspective, those arguing that the Fed should have been more expansionary during 1934–1936 are actually arguing that the Fed should have taken it upon itself to repeal FDR’s high wage policy.

-

The economic impact of the 1937 gold scare, in particular, has not received the attention that it deserves. This eighteen-month period is one of the best examples of how the gold market approach to aggregate demand can provide insights not available from the traditional monetary or expenditure approaches.

-

By 1937, he had combined an anti-inflationary program with a policy of high wages, a poisonous combination for the equity markets.

-

And the December 28 New York Times (p. 23) was echoing the conventional wisdom when it suggested (five years prematurely) that, “1936 has proved unmistakably the definite ending of the cycle of depression.”

-

On February 5, Roosevelt announced his intention to pack the Supreme Court with six additional justices

-

The court packing scheme was the first of a series of steps that greatly strained relations between the Roosevelt administration and the much more conservative financial community during 1937–1938.

-

The fear that we were headed for “another 1929”11—that is, a speculative bubble—led the administration to impose curbs on federal purchases of commodities and durable goods as a way of restraining inflation.

-

Several articles noted that the relatively high buying price of gold created an excess supply of gold for the same reason that price support programs for wheat led to grain surpluses. There was speculation that the gold sterilization policy would eventually collapse under the pressure of market forces, and that a revaluation of the dollar was almost inevitable.

-

important differences, however, between gold and wheat markets. First, the medium-term (i.e., one to five years) elasticity of supply of gold is almost certainly far lower than for wheat. More importantly, unlike wheat, gold was the medium of account in the United States, and thus FDR could not change the dollar price of gold without having a profound impact on the entire price structure.

-

Because the 1937 gold panic was in some respects the mirror image of the devaluation scares of 1931–1932, it might have been expected to increase the U.S. price level.

-

He took President Roosevelt sharply to task for having failed to foresee in January 1934 that the devaluation of the dollar by 41 percent would lead to such a superabundance of gold. If, however, we look at Professor Cassel’s earlier writings, we find that he himself failed to foresee such developments, even at much later dates.

-

We read in the July 1936 issue of the Quarterly Review of the Skandinaviska Kreditaktiebolaget the following remarks by Professor Cassel: “There seems to be a general idea that the recent rise in the output of gold has been on such a scale that we are now on the way towards a period of immense abundance of gold. This view can scarcely be correct.” … Thus the learned Professor expected a mere politician to foresee something in January 1934 which he himself was incapable of foreseeing two and a half years later.

-

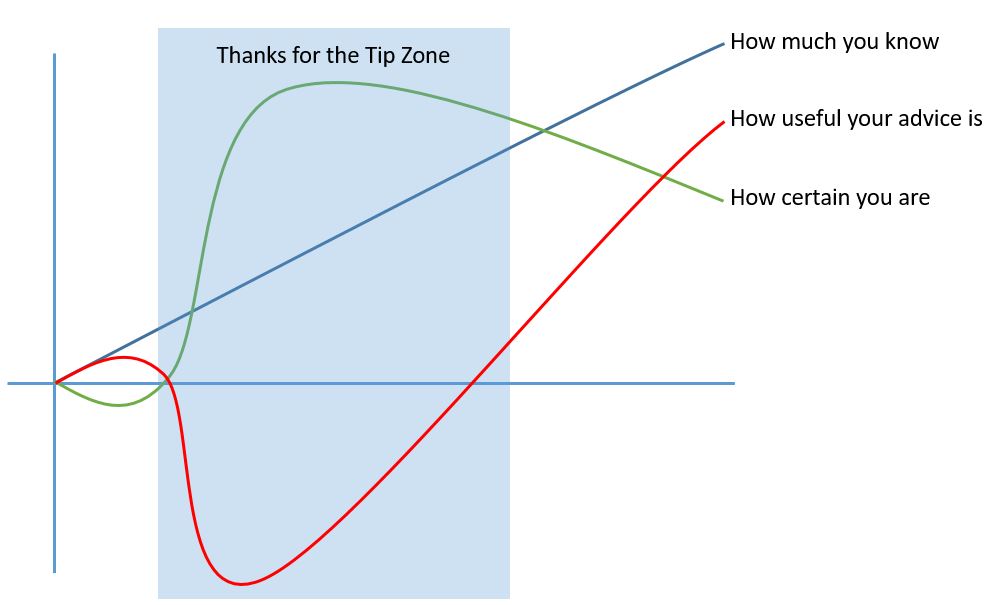

The intelligentsia generally picks up on a problem some time after market participants become aware of the problem.

-

In addition, both Soviet production and private dishoarding turned out to be smaller than what was projected during the height of the panic.

-

THE 1937–1938 CONTRACTION was roughly comparable in depth and duration to the 1920–1921 contraction, which makes it one of the most severe downturns of the twentieth century.

-

the French government had chosen to import gold rather than let the franc appreciate.

-

As with Hoover, FDR’s commitment to the gold standard prevented him from offering any effective policies for boosting the price level.

-

During the following week, stocks continued to rise on rumors of additional inflationary steps and on April 14 FDR announced a policy of gold desterilization as well as a reversal of the reserve requirement increase from the previous May.

-

These steps initiated the third phase of the administration’s macroeconomic policy. An expansionary policy was in place for most of FDR’s first term, gradual moves toward a contractionary policy began in mid-1936, and now the administration had switched back to an expansionary policy:

-

On the contrary, the denials aided market sentiment. (6/21/38, p. 29, emphasis added) The final sentence of the New York Times quotation is particularly interesting. The implicit assumption is clearly that devaluation rumors would normally boost the stock market, but that this time the market was aided by the suppression of those rumors. What the stock market most wanted was clarity. A devaluation of the dollar would boost prices, but decisive steps to restore confidence in the dollar would lessen gold hoarding, and this would also tend to raise prices.

-

Monetarists emphasize how the high levels of excess reserves reduced the money multiplier, and suggest that the Fed should have targeted the broader monetary aggregates.

-

The extraordinarily high demand for excess reserves tended to indirectly increase the demand for monetary gold, thus preventing the rapidly growing gold stocks from having the inflationary impact one might have normally expected.

-

Thus, the Depression was over even before the United States entered the war.

-

This points to another important lesson: that it is easy to confuse a lag in the impact of monetary policy with delays caused by something very different, a delay in the public’s willingness to accept that the policy change will persist.27

-

Does this more nuanced interpretation make the gold hoarding merely an endogenous factor, with no causal role in the ensuing depression? I think not,

-

The Fed’s decision to begin paying interest on reserves in October 2008 almost certainly contributed to the extraordinary increase in the demand for excess reserves (although it wasn’t the only factor). The Fed’s rationale was that they wanted to keep control over the Fed funds rate as they injected large amounts of liquidity into the banking system. This essentially meant that they wanted to prevent nominal rates from immediately falling to zero. Thus, the effect was contractionary, and at almost the worst possible time.

-

If we have learned anything from our study of the Depression, as well as the situation in Japan during the 1990s, it is that nominal rates are not a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

-

In short, low nominal interest rates may just as well be a sign of expected deflation and monetary tightness as of monetary ease.

-

But when prices started falling in late 2008 the Fed refused to adopt a higher inflation target in the United States. As a result, 2009 saw nominal GDP fall at the fastest pace since 1938. Let’s hope this is the last time the Fed adopts a policy aimed at encouraging money hoarding in the midst of a recession.