One of the most common questions that I wonder about is what sorts of savings ‘checkpoints’ people should be aiming for, especially early on in their careers.

The Inspiration

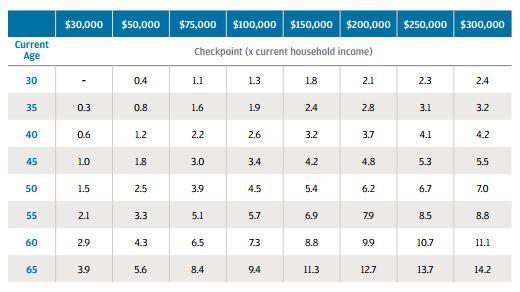

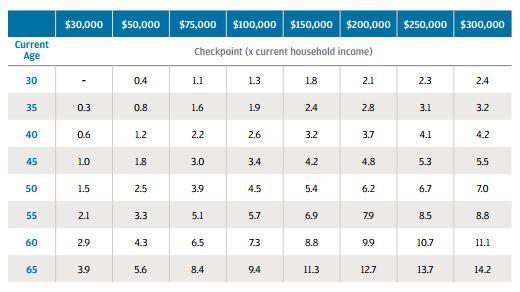

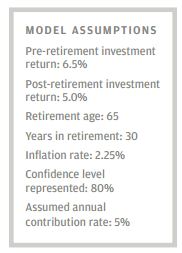

I was recently pointed in the direction of the J.P. Morgan Guide to Retirement, which I found to be a thoroughly enjoyable, if not always actionable read. It includes a slide with the same name as the title of this post.

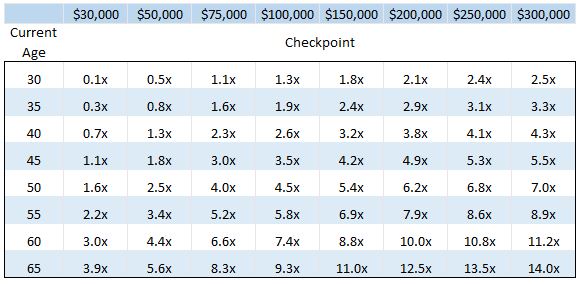

Page 15 looks like this (and do visit the entire page at the above link):

I found this to be very practicable (if it is a truly useful approximation). If a 30 year old makes $100,000, and wants to retire at age 65 that same standard of living they should have saved $130,000 by now.

The Assumptions

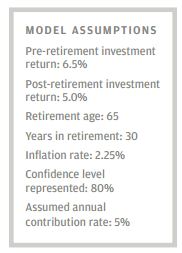

This obviously opens the door to questions about what the other assumptions are:

- Retire when?

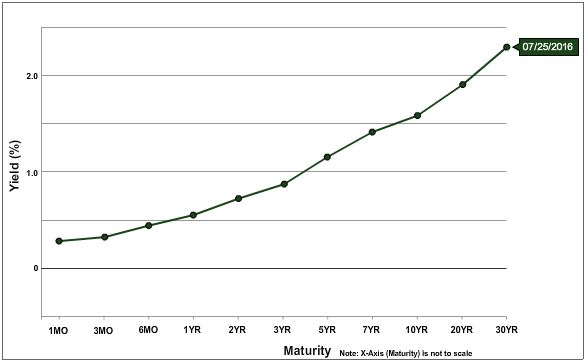

- Portfolio returns?

- Inflation?

- Retirement age?

- Years of retirement?

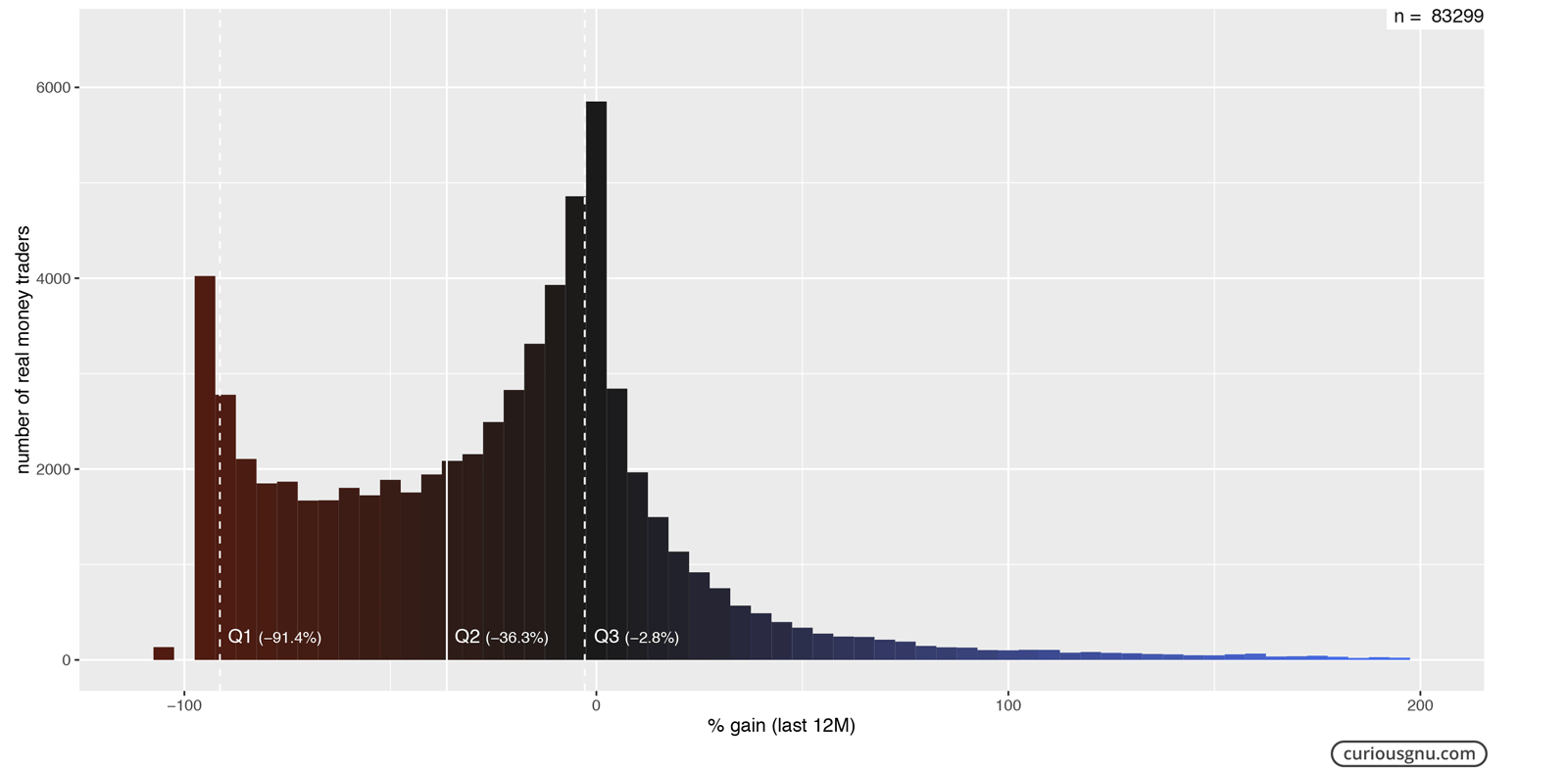

- Future contributions rate?

J.P. Morgan kindly provides us with some of those as well (though I have no idea what confidence level “80%” means).

They also include data on the assumed income replacement rates (if you make $200,000 and pay $100,000 in taxes, you have to replace only $100,000 (50%) of your income to live the same lifestyle in retirement (actually, $100,000 minus annual savings). If you make $30,000 and pay $3,000 in taxes, you have to find a way to replace 90% of your income. They also factor in social security (which has the opposite effect, as it replaces a much higher % of lower earners’ income).

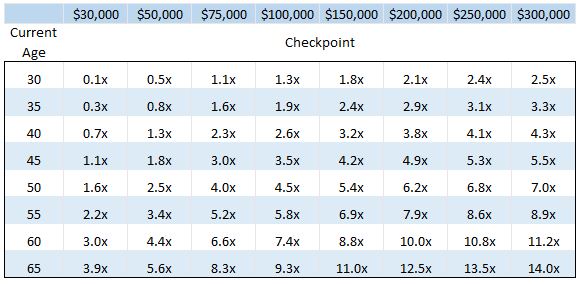

Building My Own

Like any red-blooded nerd, I realized that if I wanted to play with the model I would need to rebuild it, make it stronger.

Pretty quickly it became apparent that even if I take the other assumptions at face value, the question of tax assumptions looms large, especially:

- Are all contributions being made to retirement accounts?

- Is there a static or dynamic tax assumption (at withdrawal or other)?

Another small question, are contributions inflation-adjusted? E.g., does a 5% contribution go up by 2.25% and mean a 5.1125% contribution the next year? Equivalent to 5% on an income that increased with inflation.

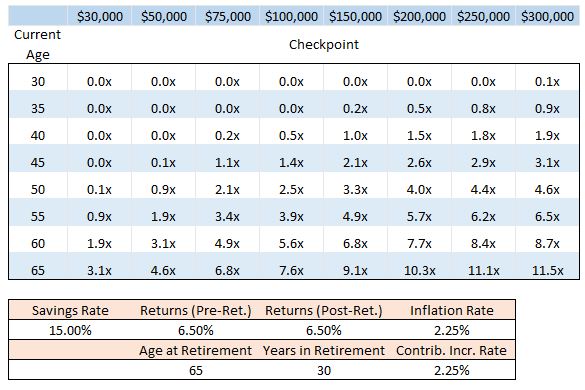

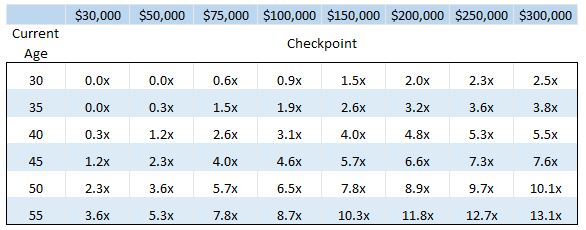

So, as close as I can figure (without doing anything smart like actually asking the authors [stay tuned]), basically eyeballing the data here, assuming the below is a pretty reasonable start:

- Yes, contributions are increased to keep up with inflation, and;

- All contributions are made to retirement accounts, and;

- All distributions are taxed at 28%

(Click for side-by-side)

New Scenarios

So now that I have my own model that works under some reasonable conditions, I can start playing with the inputs.

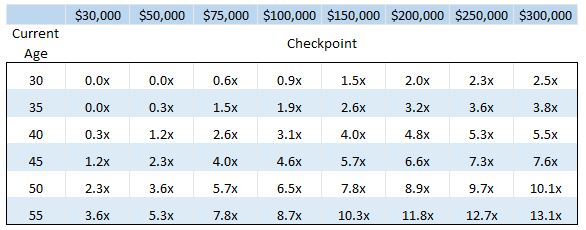

First, I like the flexibility, but prefer to keep returns equal pre and post-retirement. I think 6.5% is still reasonable. Then, what about retiring at 55 instead of 65? And what if my annual contribution rate is actually 15%?

New checkpoints! Now, there is not a linear relationship here, because of the higher savings rate, the earlier checkpoints are more forgiving, while by 55, they are much higher. Since we changed multiple inputs at once, it is hard to see from the table how much of the change came from the extra 1.5% return in retirement versus the (opposite) forces of earlier retirement and a higher contribution rate.

We also run into a problem with the income replacement rate — because J.P. Morgan was assuming age 65, Medicare was in play for all of retirement, and they assumed that social security was being taken as well. For someone retiring at 55, we need to go back and add some excess draw for those ten years. We’ll save that for another post.

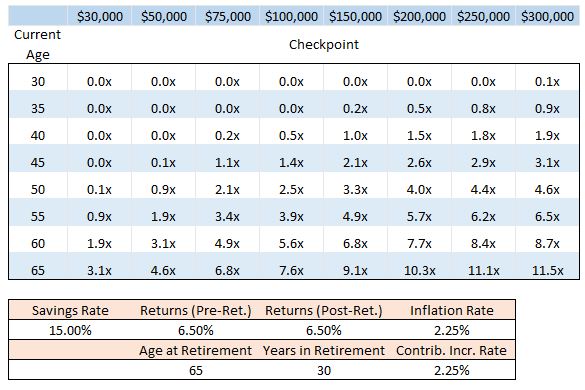

Age 65 Retirement Scenarios

So without backing into some assumptions for how much income to replace in the years before age 65, we can still play with other scenarios.

Here is 15% savings rate with 6.5% returns.

It doesn’t take much teasing of the data to find an interesting conclusion – if you are going to retire at 65 and are able to consistently save 15% throughout your working life, it’s important to get started by 35, but it is okay if you haven’t made much progress yet.

On the flip side of the coin, if you’re approaching 50 and make $200-250k (and want to maintain that lifestyle), you best be closing in on a million dollars, or planning to save even more going forward.

The Limits

This model is incredibly simple, major variables like taxable accounts are omitted entirely. I’ll probably revisit this at some point, including inquiring about the actual assumptions the folks at J.P. Morgan used, building in better ‘early retirement’ capabilities, making my own estimates for income replacement rates, etc..